IC3 Project: Community Needs Assessment of Baton Rouge and Hidalgo

IC3 Project Overview: Interviews with Community-Based Organizations

The past decade of disaster preparedness has focused heavily on individual and family readiness, rather than strengthening of community networks and social programs to support the community. As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic and long-evidenced through research on disaster preparedness, community resilience is built on a foundation of strong relationships and networks among organizations and individuals who understand — and are trusted within — a community. Without such foundation, when a catastrophic event such as a hurricane, or pandemic occurs, vulnerable communities can be found facing a preparedness gap. The preparedness gap is the gap between community and individual concern about events and their ability to prepare for disaster events. This gap is particularly profound among communities of color and groups who face systemic inequities related to economic stability, education, health and healthcare access, and other social determinants of health (SDOH). Funded by the Walmart Foundation, Healthcare Ready’s research on the Impacts of COVID-19 on Communities of Color (IC3) sought to gather stories from community-based organizations (CBO) to understand the challenges that communities are facing during COVID-19, and to elucidate strategies for the private sector and public-private coordination initiatives to support community resilience. This summary is an overview of the research undertaken with CBOs to identify:

(1) Preparedness gaps and challenges that existed for communities before COVID-19; and

(2) Gaps and challenges that were significantly exacerbated or directly caused by COVID-19.

The gaps and challenges raised by CBOs across 30 interviews in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Hidalgo County, Texas surfaced the following as the most pressing needs among vulnerable communities:

- Food insecurity;

- Long-term housing and utility relief;

- Unemployment or employment uncertainty;

- Resources to address mental/behavioral health support; and,

- Access to healthcare (including equitable access to COVID-19 healthcare resources).

CBOs also identified the following areas of need for their organizations to better serve their mission and help their communities recover from the pandemic:

- Enhanced partnerships and networks; and,

- Increased sustainable funding.

The stories and voices captured in the IC3 research are a vital tool to help government and policy makers to take actionable steps toward building more resilient communities. The final Community Needs Assessment and suggested recommendations from this effort are in development and will be published in the next few months. Meanwhile, click on the sections below to learn more about the immediate findings and impacts:

Approach and Methodology for Identifying Interviewees

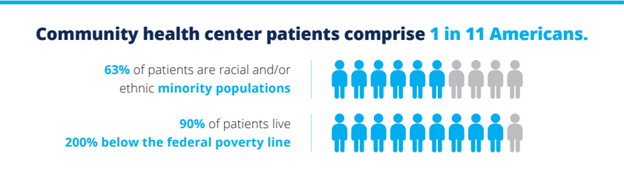

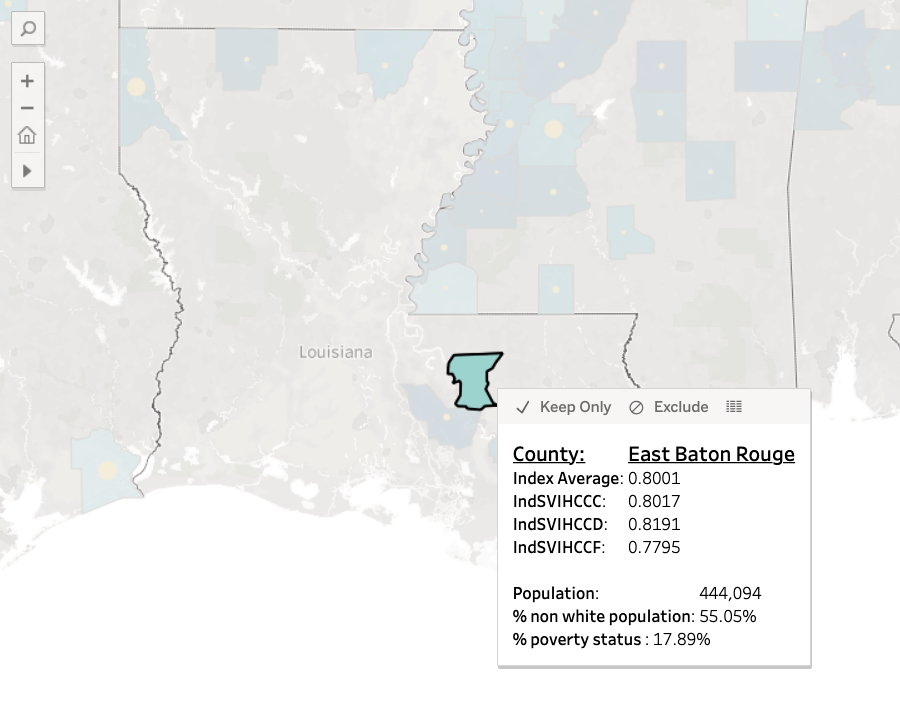

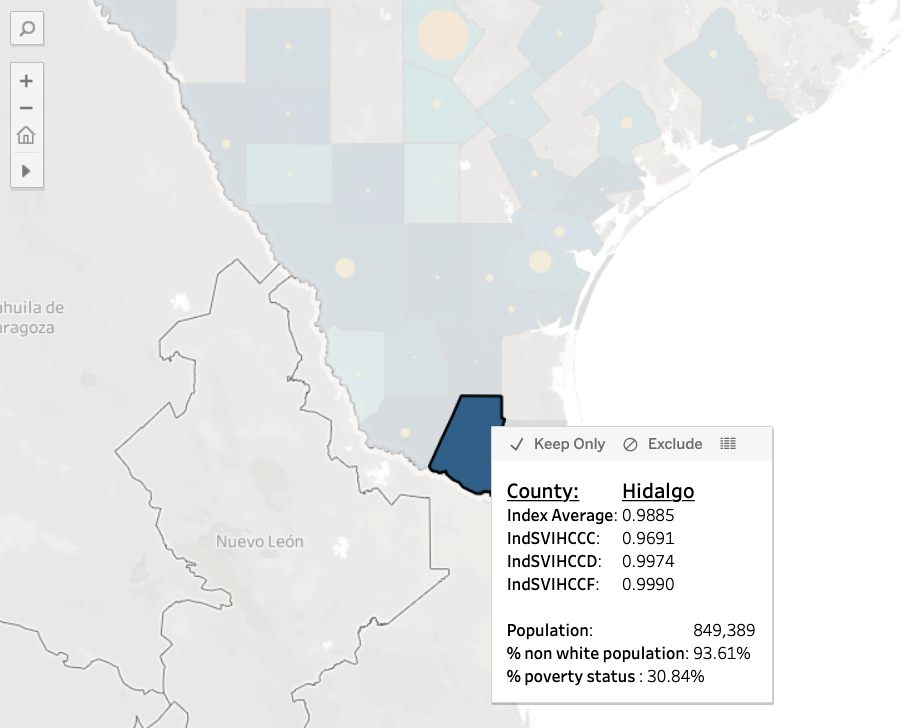

Prior to identifying individuals to interview, the team selected two geographic regions of the US on which to focus based on a calculation of their relative likelihood for negative impacts from disasters and COVID-19. Data from a combination of the following indices were used in this approach:

- CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index;

- COVID-19 case and death counts;

- Composite Health and Healthcare Index developed for this project to inform pharmacy and hospital access; and

- Level of exposure and frequency to natural hazards such as hurricanes and flooding.

The vulnerability assessment surfaced several regions of interest. For the purposes of completing this study within resource and time constraints, the following regions were selected as primary areas of focus: Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Hidalgo County, Texas.

CBOs in these two regions dedicated to providing services to vulnerable populations were identified via Google search of CBOs in respective regions and through recommendations from partners at:

- National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (NVOAD);

- National LULAC Network;

- Catholic Charities USA; and

- NAACP.

More than 130 NGOs were invited to participate in a 30-minute phone interview representing the following areas. See Table 1: CBO Mission Areas for IC3 Interviews:

- Churches and Faith-Based Organizations

- City/County Employment Agencies

- Social Service Programs

- Community Centers

- Disability Assistance Resource Programs

- Emergency Management Agencies

- Food Banks

- Grassroots / Local Nonprofits

- Healthcare (e.g., Clinics for Underserved Populations)

- Homeless Shelters

- Local Chapters of Community/Advocacy Organizations

- Public Health Department (Or Healthcare Coalitions)

- Rape Crisis/Domestic Violence Shelters

- School Systems

Critical Needs for Communities and CBOs

In total, 17 CBOs in Baton Rouge and 13 in Hidalgo responded to interview requests that were conducted by phone and transcribed into notes in an Excel spreadsheet. A grounded theory approach was used to code common themes across participants, which were categorized under the following three areas:

- Individual Needs – Areas of relief sought/needed by individuals in the local community;

- Barriers to Meeting Individual Needs – Systemic barriers to individuals achieving health equity;

- Needs for Community-Based Organizations – Areas of need identified by CBOs to sustain or expand existing services to meet growing needs during and beyond the pandemic.

Below are excerpts of conversations with the interviewees about their community’s most urgent needs and challenges.

Individual Needs

How we define the issue: Inadequate or inconsistent access to “enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members,” or unstable availability of nutritional foods.1 Being faced with food insecurity is also tied to having to choose between paying for food and other basic necessities such as shelter or medical treatment.2

Voices we heard: “[food security] reared its head almost immediately after the shutdown,” recalled a non-profit organization dedicated to reducing poverty and food insecurity in Baton Rouge.

At least 12 interviewees in Baton Rouge cited food insecurity as an area of need, with four of those organizations citing it as the most pressing need. All four interviewees from organizations providing food relief reported expanding or increasing services to their community during COVID in both Baton Rouge and Hidalgo. The same organization mentioned above also noted that food insecurity, “was especially apparent and dire in the school system.” Added another organization offering legal representation to children, “After a full year of school lockdown, school closures are impacting families who lost two meals that kids would’ve gotten from school.”

One Hidalgo County school administrator described how their district stepped up to address food insecurity, saying, “The school district has been providing food to students and their families through the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) program. Through this program, the families are given seven days’ worth of food. Initially we were giving families no perishable food because there was not enough personal protective equipment for cafeteria workers, but now we’re serving hot food to families.” They noted that upon first transitioning to serving hot food, “there was a higher incidence of COVID infections among food service workers, so we had to close the program until every worker was cleared.”

How we define the issue: Housing and utility needs refer to challenges or the inability to pay for rent, mortgage, or basic utilities (water, electricity, etc.).

Voices we heard: At least six organizations in Baton Rouge and seven organizations in Hidalgo cited housing and utility relief as the most pressing need. Referencing COVID-19 relief funds that have been distributed via stimulus checks and into funding for entitlement programs, the Policy and Advocacy Director of one food bank in Baton Rouge noted, “These benefits, to some extent, have addressed housing insecurity, food insecurity, and utility assistance. However, these problems will persist long after the pandemic, and may be made worse as a result. The roll back of benefits/aid should be framed as ‘through the end of the economic downturn’ instead of ‘through the end of the pandemic.’”

A pastor of a Baton Rouge Baptist church expressed concern about the government, “not continuing programs to stop evictions.” The biggest threat to people’s future needs, he noted, was “the threat of not knowing how long people can continue paying their bills.” “The moratorium on evictions has, up to this point, prevented a homelessness crisis. However, this is a band-aid solution,” noted the president of the local chapter of a national social services network.

3. Unemployment or Employment Uncertainty

How we define the issue: Persons directly affected by pandemic-related job losses, or those who were tangentially affected by pandemic-related job loss within their household.

Voices we heard: According to a study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the majority of jobs lost in the economic shut down caused by the pandemic have been in industries that pay low average wages (e.g., restaurants, gasoline stations, general merchandise stores). This is significant because workers from communities of color are overrepresented in low-wage jobs, making individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic or Latinx, Asian, or other ethnic minority particularly vulnerable to layoffs during the pandemic.

This was evident in the stories shared by interviewees, and the cascading impacts on households following job loss or future unemployment uncertainty. “Many gig workers, or service industry workers have lost steady income and are finding themselves dealing with food insecurity,”noted one prominent food bank in Baton Rouge. Another Baton Rouge interviewee commented, “The service industry has also been hard hit with their workers being displaced. People in the service industry usually have more than one job in the industry and have either lost all forms of income or having to deal with a severely pared down single stream of income.” In Hidalgo, nine of 13 organizations interviewed cited employment as a top need during and following the pandemic. Said one school district representative, “Students’ families are suffering from unemployment, especially female parents as they have had to choose between working and child rearing.”

4. Mental/Behavioral Health Support

How we define the issue: Mental and behavioral health needs surfaced as comments related to increased depression, anxiety, and poor emotional or mental health overall.

Voices we heard: Pandemic-related challenges such as social isolation or changes in job and financial status have significant impacts to deteriorating mental health, and anecdotally corresponds to an increased need for care. Residents with low socioeconomic standing along with ethnic minority populations are feeling the brunt of the impact. “With virtual schooling and stay-at-home orders, more people are experiencing depression, anxiety, and substance abuse,” noted a CBO in Baton Rouge dedicated to the provision of mental health services. At least four interviewees in Baton Rouge cited the lack of infrastructure to support mental health in their community, two of whom felt that this was one of the biggest needs people in their community experienced due to COVID-19.

Pervasive poverty further compounds mental health needs, as it simultaneously results in mental health challenges and presents a barrier to accessing resources for those mental health challenges. Noted by the president of the local chapter of a national organization offering social services programs, “The community is not a greedy community and deserves to be supported in best way possible. In order to address these issues, we need to first recognize that the poverty rate is high in this area and beefing up counseling staff alone may not work because counselors typically only work during regular business hours, when everybody else also works. How can increased staff lead to an increase in therapy if that service is not available after hours or on the weekends?”

5. Healthcare access, including equitable access to COVID19 healthcare resources

How we define the issue: In the context of interviews, this theme relates to equitable access to healthcare information and provider services, including COVID-19 related services such as testing and vaccines.

Voices we heard: One interviewee from a local, government-based health initiative noted,” [there are] healthcare deserts in some parts of Baton Rouge,” adding, “the lack of widespread availability in points of healthcare has particularly been highlighted through the struggles in access and obtaining COVID testing and vaccines.”

In Hidalgo, a school administrator said, “There is a gap in long-term healthcare because cost is a barrier to seeking help, and the paperwork needed to access care [acts as] a stumbling block because of citizenship status.” At least five organizations in Hidalgo cited challenges in accessing healthcare, with one of those organizations substantially modifying their work to address this impact of COVID-19. A director of a local health clinic for the underserved in Hidalgo said, “COVID testing is an ongoing need … we need access to free, accurate testing. Testing numbers have dropped because the resources are not there and have shifted to focus more on vaccines. The scarce resources shifted to vaccination are still not enough,” pointing to a lack of infrastructure in staffing and supply to meet the demand for vaccines.

Barriers to Meeting Individual Needs

How we define the issue: Technological barriers revolve largely around internet access, including the challenges related to equipment and infrastructure needed to obtain affordable, reliable, internet.

Voices we heard: Technological access is particularly important when contextualized as a barrier to meeting other needs, such as online learning, virtual employment, and seeking help online (e.g., for COVID-19 prevention information or for telehealth purposes).

One Hidalgo-based community organization noted that while resources exist to provide community relief for basic needs, technological barriers can prevent families from getting the help they need. COVID-19 vaccine information, or applications for rental assistance, are examples of available resources that can remain inaccessible for those who have a persistent lack of internet access or may be unfamiliar with navigating online applications.

Another representative from a Hidalgo school district emphasized that the lack of access to technology has “been a nightmare” for students, as schooling transitioned to a virtual environment. The same school district highlighted that while the school handed out laptops to some students, they were unable to meet the demand, and had to create a wait list for students needing tech resources.

In Baton Rouge, the lack of technological access was cited in more than a quarter of the interviews as a barrier to accessing resources necessary to mitigate existing needs. As one community organization pointed out: Limiting access to information through only virtual means “assumes that people have internet at home and a working computer,” which is often not the case in greater Louisiana where approximately 150,000 children were found to “lack access to high-speed internet in their household” and nearly 47,000 children “had no computer at all” as of 2018.

How we define the issue: Childcare as a barrier to meeting individual needs refers to limitations or trade-offs related to needing to supervise children. This can, for instance, refer to work schedule constraints on a parent or guardian to ensure that their children have adequate supervision and care, or limitations in being able to pay for childcare when needed.

Voices we heard: At least seven interviewees in Baton Rouge cited the lack of access to childcare to be a barrier to seeking assistance, four of which felt that this was one of the biggest needs people in their community have experienced due to COVID-19.“Childcare has also been a growing need as children are in virtual learning environments and parents are either working from home or have to go to work,” noted the president of the Baton Rouge chapter of a national social services non-profit. He continued, “Many are forced to choose between working and caring for their children. There needs to be a solution for virtual learning environments that help parents and the students.” “Childcare has also been a big issue since people have to go to work and don’t have anyone to watch the children,” noted the administrator of the Southern Texas chapter of a national social services nonprofit. They noted having to “transition [our] afterschool program to serve as a quasi-school program, prioritizing children of first responders and other healthcare workers.” Some interviewees also noted the disproportionate effects childcare has had on women in their community, “as they have had to choose between working and child-rearing,” said one representative from a school district in Hidalgo. Several interviewees also brought up issues in accessing public services programs, mentioning, “… if [my clients] are able to go to a place to receive assistance, there are usually long lines, but they do not have time to wait in the line all-day since they have to care for the children.”

3. Infrastructure to Access Mental Health

How we define the issue: Infrastructural barriers to access mental health services includes the availability of qualified mental health providers (including time and within reasonable geographic distance); ability to pay or having healthcare coverage (insurance); and lack of information to services available within a community; etc.

Voices we heard: Four organizations in Baton Rouge said that a lack of mental health support stood in the way of addressing their communities’ unmet needs, with two of those organizations citing stigma against receiving mental health to be a problem in the community. An administrator of one homeless advocacy organization in Baton Rouge commented, “Luckily, the base shelter has a [a clinic] on site, and we also try to work through Medicare and Medicaid, but Medicare and Medicaid are often a struggle especially in regards for mental health care because providers often do not authorize services.” A local government official in the region also echoed this concern saying, “Not many counselors accept Medicaid, or patients cannot afford to pay out of pocket for session.”

Additional barriers described by the administrator of a health clinic in Hidalgo, include the need for additional funding for therapists. “As the need for mental health counseling has increased dramatically, the load on limited counselors increased and is causing burnout. If counselors are burnt out, they cannot provide quality services to their clients. Not only would funding be beneficial for more therapists, but it would also serve for additional staff,” which they described as being primarily volunteer physicians who are older and could not practice in-person during the pandemic.

How we define the issue: The topic of misinformation, non-reliable information, or mistrust in information, arose around COVID-19 education and eligibility for services related to COVID-19 testing and vaccines.

Voices we heard: Two out of the three interviewees who cited lack of information contributing to misinformation in Baton Rouge, felt that this was one of the biggest needs people in their community have experienced due to COVID-19. Noted by a representative from the Baton Rouge chapter of a national society for professionals, “In regard to the vaccine, there are three main barriers: Misinformation, lack of understanding, and distrust.” Similarly, the pastor of a local Baptist Church spoke about, “health disparities caused by misinformation,” and pointed to, “skewed levels of vaccine administration,” in the local community caused by misinformation, and “lack of trust in the system and messengers.”

In Hidalgo, a border town in Southern Texas with a high-immigrant population, an administrator with a housing organization described the problem of, “hesitancy around seeking healthcare and lack of trust in the system [causing] people to not believe the severity of the virus and/or are not afraid of getting sick.” Another administrator at a local school district pointed to how they can combat mistrust in the community by leveraging their trusted relationships within the community, saying, “We would love to partner with more organizations to reach the community since the school district is in tune with the community and are trusted by the community. We have access to the families and neighborhoods.” Evidenced by what they’ve already achieved in their community, they added, “We recently held a virtual training for 150 parents where a trusted physician came in to speak about vaccine misinformation, as well as a tax attorney who came to speak about delinquent taxes and the upcoming tax season.

These events are helpful because the information is relayed by word of mouth to other community members that may not have had that information before.”

Needs for Community-Based Organizations

How we define the issue: Partnerships are the relationships between CBOs and respective partners (public and private sector) that offer services complementary to the CBO’s own mission areas. Partnerships are vital during an emergency when individuals and organizations may need to quickly identify a contact to coordinate support among individuals and groups.

Voices we heard: The challenges and far-reaching benefits of enhanced partnerships resonated across several interviews. At least 12 interviewees in Baton Rouge cited a need for increased awareness of partner organizations, three of which felt that this would help address the unmet needs of the people in their community. In general, larger organizations and those with extensive partnership networks (i.e., chapter groups of larger national advocacy organizations) were able to reach more people and even expand services, in comparison to smaller, lesser networked groups.

During the pandemic, when community reliance on services provided by these CBOs increased, resilient organizations were able to partner with other CBOs to meet the increased demand. A school administrator describing their situation in Hidalgo County said, “towards the beginning of the pandemic, a couple restaurants reached out to partner in distributing food to the community, but that effort did not last so we’ve started partnering with [nearby] school districts,” some of which have government support, and some that do not. But, they continued, “these partnerships are ultimately informal. They need to be formalized, not only with other school districts, but other non-profit partner and social service agencies. We would love to form new, formal partnerships, but we do not know how or to who to reach out. There is a feeling that no one knows who the stakeholders are in this area.” Despite this, she added, “the children do really well in the circumstances. They overcome the odds.”

Another Hidalgo organization focused on providing employment services described their outreach efforts expanding into several areas, saying, “[We’re] partnering with higher education institutions and food pantries. The high demand for assistance is outpacing the supply of assistance which is making it difficult to get everyone covered.”

How we define the issue: Funding refers to the financial resources needed for a CBO to sustain the operations that fulfill their mission.

Voices we heard: Several CBOs in both regions reported being strained under increased demand for their services. At least 16 interviewees in Baton Rouge cited increased funding to be a need for their organization, seven of which felt that state or local level changes would address this problem.

Many organizations that rely on individual donations or fundraising events experienced a decrease in funding during the pandemic. Mentioned by one food bank in Baton Rouge, “Many agencies are tapped out on funding . . . Most funding is a one-time donation gathered through fundraising [pushes] throughout the year.” With increased demand for assistance, many organizations expressed that they struggled to keep up with the increased workload. “Funding and resources are concentrated at the state level and it is extremely difficult to advocate for proper funding and allocation of resources,” noted one local government-based CBO in Baton Rouge. And noted in the same spirit by a health clinic in Hidalgo, “While we do receive funding from precincts, we’re no longer able to request for additional funding. With increases in operating services, we should be able to solicit a corresponding increase in funding. Counties need to be equipped with increased capacity to properly fund clinics.”

Summary of Findings and Next Steps

Immediate takeaways from these conversations revealed the following areas represent the most pressing needs for communities like Baton Rouge and Hidalgo Counties:

- Addressing food insecurity;

- Providing long-term housing and utility relief;

- Addressing unemployment or employment uncertainty;

- Creating resources to address mental/behavioral health support; and,

- Increasing access to healthcare (including equitable access to COVID-19 healthcare resources).

CBOs also identified the following areas of need for their organizations to better serve their mission and help their communities recover from the pandemic:

- Enhanced partnerships and networks; and

- Increased sustainable funding.

Several other themes also emerged in these conversations that will be assessed in the final Community Needs Assessment specific to each region, including:

- Transportation needs;

- Challenges in accessing adequate healthcare due to hesitancy/mistrust of the system and inability to pay for services (e.g., uninsured patients); and,

- Concerns around immigration status and lack of understanding of how to navigate the healthcare system contributing to hesitancy in seeking care.

Disasters underscore the need for strong partnerships and trusted relationships within a community to help support those who may be most vulnerable in emergency situations. The stories and voices captured in the IC3 research are a vital and essential tool in helping government and policy makers to make progress and take actionable steps toward building more resilient communities. We look forward to sharing this final assessment with community leaders in Baton Rouge and Hidalgo Counties to help them understand how groups are connected; where additional relationships can be fostered to fortify networks in advance of the next disaster; and to promote interventions and mitigation plans that meaningfully close the preparedness gap for communities of color and other groups who remain especially vulnerable in a disaster.

1 Feeding America, (2018). Food Insecurity in Louisiana. Feeding America. http://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2018/overall/louisiana

2 Ibid.

4 Butkus, Neva, (2020). Separate and Unequal: Students’ Access to Technology in the Time of Coronavirus. Louisiana Budget Project. https://www.labudget.org/2020/05/separate-and-unequal-students-access-to-technology-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/

COVID-19 and Equity Project

Read more about our work on equity during the pandemic: COVID-19: Equitable Response and Recovery