Healthcare supply chain management is a critical part of any disaster response. From natural hazards to disease outbreaks, we rely on a stable supply chain to create and move response supplies and to maintain standard operations for the millions who rely on products like pharmaceuticals for chronic health needs.

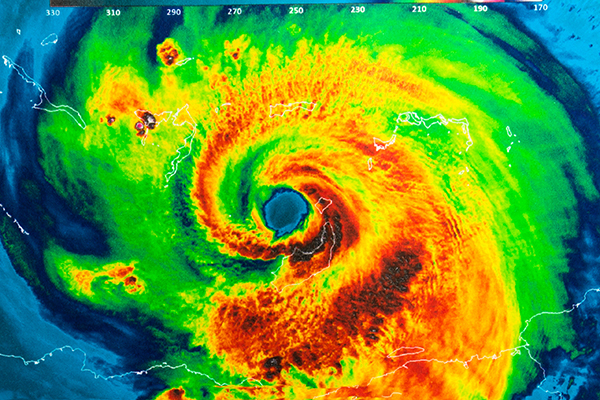

When hurricanes hit Florida, for example, it’s key to keep pharmaceutical factories running, ensure distribution centers are safely staffed and operational, and make sure “last mile”1 deliveries make it from those distribution centers to hospitals and pharmacies (even if it takes a duck boat or two).

But during large-scale disease outbreaks, which can impact multiple countries and last for months or longer, disaster supply chain management can shift. Moreover, the truly global scope of how we get products comes to the fore.

That’s why in outbreaks like that of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), we must think globally to appropriately respond locally. This is because global supply chains – especially of medical supplies and pharmaceuticals – are incredibly complex. So even while we continue to prepare at home, keeping the global supply chain moving must be a priority for the US to ensure we have supplies, not just for impending spread of 2019-nCoV, but for managing chronic needs of millions across the country and the world.

The outbreak of 2019-nCoV poses particular challenges due to the amount of industrial manufacturing in China, where 2019-nCoV is most widespread. Many are particularly worried about the resilience of healthcare supply chains due to the amount of pharmaceuticals and other medical supplies sourced from China. This is not an entirely unfounded concern – about 13% of the world’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing facilities are located in China, and some portion of 80% of the world’s APIs are produced by facilities across China and India.

However, focusing on the production quantities of one country alone is not useful for countering a disease outbreak. The inherently modular globalized supply chain – in which raw materials may be sourced from multiple countries, transformed in others, formulated into a product in others, then assembled/finished and shipped worldwide – makes it hard to attribute anyproduct to a single country. Especially for medical products.

Instead of focusing on the amount of drugs sourced from China alone, we need to work to understand operations and potential vulnerabilities that manufacturers face in producing and transporting goods in the region and globally. That’s thinking about questions like “What are anticipated impacts on workforce, and how does that translate to production?” and “How are travel restrictions and border closures limiting the flow of goods?” Then we need to take action to reduce those vulnerabilities.

We already know that healthcare supply chains have shifted during this outbreak, with manufacturers adjusting operations to mitigate risks to global supply of critical products and taking steps to protect their employees and businesses. Many have surged production, some have altered proportions of goods they produce, and others have driven development of medical countermeasures, like vaccines for trials.

As we respond to 2019-nCoV, we must keep these supply chain shifts – and their global scope – in mind. And instead of asking how much producers are making right now, we need to weigh the important questions about what will allow them to continue to produce in the future.

“Last mile” refers to the movement of goods from a distribution center (DC) to the final delivery destination. For medical supplies like pharmaceuticals and personal protective equipment (PPE), this is usually the delivery from a DC to healthcare provider like a pharmacy or hospital.